The Unintended Consequences of Proprietary Equipment on Construction

Contractors and architects often select proprietary equipment to achieve short-term financial goals and streamline development, but they should be mindful of the hidden dangers in closed-system construction. Proprietary equipment determines the building’s obligations and the owner’s ability to fulfill its duties, sometimes permanently.

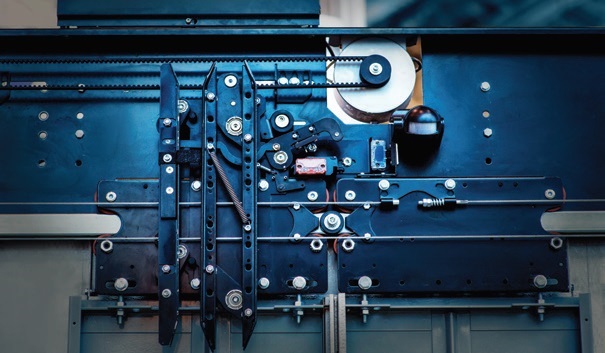

As its name suggests, proprietary equipment originates from (and whose rights are owned by) the manufacturer. Proprietary components exist across construction industries, including vertical transportation and fire and safety. Proprietary equipment includes software and hardware, but can affect the site’s attendant specifications, such as building hoist ways or access rooms.

In practice, independent vendors and manufacturers define proprietary equipment as “closed” due to its accessibility restrictions, including others’ abilities to maintain, service or bid for contracts on proprietary systems.

“Proprietary equipment is manufactured by a sole source entity that may not be available on the open market to all,” explains Charles Meeks, president and CEO of Delaware Elevator and Delaware Elevator Manufacturing. “If and when it is made available, the sole source providers charge an exorbitant price for the software or components that force the building owner to not have competitive options.”

The alternative is software and hardware that offer open architecture. In non-proprietary models, the originating vendor readily sells all components at competitive prices to any qualified party.

Likewise, any qualified vendor can service hardware and software. Accompanying training, if necessary, is accessible and the building’s specifications are unrestricted to the unit’s maintenance.

Implementing proprietary equipment is standard practice for most contractors and architects for a variety of reasons, including its upfront low cost and its integration in architects’ drafting programs. Proprietary manufacturers sell at competitive prices and even provide professional development about how to include their equipment at industry conferences. Yet, what contractors and architects initially save in money and time may be short-lived when building owners experience longer- term consequences.

“The last big building we installed had two elevators. The contractor got the lowest price, but the warranty didn’t include five-year testing,” says Robert Boyce, facilities director at Frostburg State University, where he oversees the maintenance and development of numerous institutional buildings for the campus. “While the contractor got a good deal, I got stuck with the elevator maintenance. Then the manufacturer closed its local office.”

After this experience, Boyce committed new building specifications to non-proprietary systems only. As a result, he’s partnering from the outset with a construction firm and consultancy on a current project to ensure its non-proprietary design.

Public entities such as higher education institutions and government agencies are leaders in changing the proprietary and non-proprietary landscape during design, construction and maintenance.

Mark Yako, GAL Manufacturing Northeast regional sales manager, notes: “The government is said to be overpaying for equipment, but it’s paying for longevity.”

Meeks agrees that “many of the government agencies we work for specify non-proprietary equipment wherever they can. They write in non-proprietary on their specifications; they’ve been burned in the past, so they keep proprietary equipment out whenever possible.”

As building owners experience long-term consequences of proprietary equipment installation, which may include escalated maintenance and repair cost—up to and including whole system replacement—construction and design partnerships are changing. Building owners participate directly with contractors and architects; they also hire consultants to advocate on their behalf.

“Normally, when I’m brought in as a consultant, they’re not happy,” says Sheila Swett, executive director of the International Association of Elevator Consultants, and owner of Swett & Associates and Elevator Technical Services. Swett consults with owners and partners with architects primarily on larger projects, such as universities or convention centers, to ensure the reliability and safety of the equipment while promoting the building owner’s interests.

“You have to look at the long term and shift to being more receptive to putting in a system your client can work with,” Yako says.

The questions building owners should be asking architects are the same ones architects and contractors can pose themselves: What are the ramifications to serviceability and cost of the equipment? What are the monthly service costs every three years, five years and 10 years?

As Meeks observes, “To me, it seems like a duty to research the products for the building. They do it every day for windows, carpet, etc. They should do it for elevators and fire systems and software in the building, too.”

What’s at stake is not only the building owner’s pocketbook, but also the architect’s and contractor’s reputations and client relationships.

Importantly, proprietary equipment is not a foregone negative conclusion. “There are plenty of experiences where owners of proprietary equipment have had positive experiences, but there are also plenty where companies are doing business because they must,” Yako notes.

As buildings get smarter and more automated, demands for proprietary or non-proprietary components increase. When contractors and architects consider long-term maintenance, it’s important to note that they can retain their preferred vendors, including proprietary manufacturers, to install non-proprietary equipment. Meanwhile, independent vendors are currently working to train architects in non-proprietary design.

As a result, while contractors’ and architects’ routines change to promote the wealth of the end user, their habits may not be as significantly altered as initially feared.

Originally published in the March 2019 edition of Construction Executive.

Liz Mathews is a business writing consultant for Kencor, Inc. Elevator Systems, West Chester, Pennsylvania. For more information, visit kencorelevator.com or check out the ABC Elevator Contractors Council at abc.org/membership/ elevator-contractors-council.